Originally posted April 2013 on my dedicated History Blog (no longer running), I thought it might be of interest to those who delve into historical fiction, only to find themselves… bemused. Unable to keep it politely brief, I have tried to keep it light.

So, let me introduce the game…

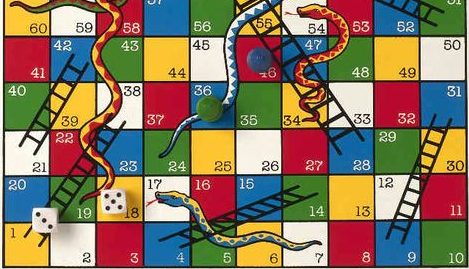

The Snakes & Ladders of The Medieval World

Throughout the Medieval period, and far into the Modern, the English upper classes played the Gentry Game. Its aim was threefold:

- to keep their patrimony intact (the land inherited from their ancestral fathers).

- to increase their estates.

- to climb the social ladder from Gentleman, whose unearned income ensured they kept their hands clean, to Knight, if only for the one life, to the higher nobility – Earls, Viscounts and Dukes – whose titles descended like genes with the blood.

As with any game, there were ‘cheats’ available i.e. shortcuts. But there was also that lurking snake that would send the unwary rapidly back down to earth where, as yeoman farmers, they must messy their hands.

The Rules (only one)

To present the image of honour. Present the image, because behind that façade hid all manner of deceit. Yet that deceit was the prime lurking snake, for to be caught in dishonour ensured a rapid descent.

How to Play: Levels of Gentry

Gentleman, esquire, knight, baron, the terms are familiar, in part due to the dramatised versions of Jane Austen and the lives of the Tudors. Yet the various ranks of the English Peerage and Landed Gentry can cause confusion, particularly since their usage has evolved over the centuries. So to clarify matters, here is the Ladder. But first a definition…

Gentry

Apart from the upper levels of the clergy, who are a case apart, this generally denotes people who had no need to work, their landed estates being sufficiently large to provide an income in the form of rents. However, there was a rider to that: they ought also to be well-born families of long descent. All Gentry, with or without title, are deemed ‘Upper Class’.

Gentleman

Generally regarded as the lowest rank of the English gentry, regardless of actual family origin, the younger sons of the younger sons of peers, knights, and esquires were grouped together as Gentlemen. At such a remove their inherited estates might be pitifully small, formed from ‘acquired lands’ (more anon). But if it provided an income without bending the back, Gentlemen they remained. Yet, let them once dirty their hands by turning the soil and down they must go – now yeomen and out of the Game. Yeoman is a late (Tudor) term.

Esquire

Despite it’s now a general form of address for any untitled man, when first applied in late 14th century it still retained its feudal sense as an apprentice knight. Thus to be a mesne lord, i.e. lord of a manor, was per course to be an esquire.

The Tudors, obsessed with rank and order, applied it specifically to

- the eldest sons of knights, and their eldest sons in perpetuity

- the eldest sons of younger sons of peers, and their eldest sons in perpetuity

The Tudor monarchs also bestowed the title as honorific to all attendants upon their own person. It was also granted to those holding the sovereign’s commission of military rank captain and above.

Knight

This was not a hereditary title but was granted, usually by the king, though also by one’s liege lord, for services to Crown and/or country, usually military.

The knight at this period was still a mounted warrior and expected to fight alongside the upper nobility. The Edwardian reigns (1272-1377), three generations of English kings each with an interest in all things Arthurian, saw an increase in the orders of knighthood and accompanying codes of chivalry. The knight was the lowest of the titled nobility.

Hereditary Knight

Relevant only to Continental Players. In England, from 1611, its place was taken by the baronet.

Baron and Baroness

Lowest of the hereditary titles, it originally denoted a tenant-in-chief, i.e. one who held land – by military service – direct off the king. As such, a baron was obliged to attend the Great Council, the advisory body to the king. By 13th century this Council had developed into a recognisable parliament to which the barons were ‘summoned’. Parliament subsequently divided into the Houses of Lords (where sat the barons) and the House of Commons (where sat the elected gentry, 2 knights per shire).

Viscount and Viscountess

This title was borrowed from Old French which in turn derived it from Medieval Latin. It translates as ‘Deputy to the Count’.

Not used in England until 1440. Previous to this the viscount’s administrative duties were performed by the sheriff, one of the most ancient of English ranks. Initially the title of Viscount was not hereditary but was awarded for a specific cause.

Earl and Countess

Oldest of the English hereditary titles. Akin to the Scandinavian ‘jarl’, i.e. a chieftain set to rule a region in the king’s stead. From the 10th century it replaced the Anglo-Saxon ‘ealdorman’ used to denote a noble who governed an earldom on the king’s behalf.

By the time William conquered and quartered the land and the English (1066), earl had become the equivalent of the European duke. But with King William came a change to the administrative structure of England, effecting a change to the earl’s role. No longer did he govern a region, but now only a lowly shire. This demotion provided a contributory cause to Ralph de Gael’s rebellion of 1075. His father, Ralph the Staller, had been Earl of East Anglia, but all he’d been given were the two counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. Michael de la Pole, created earl in 1385, had an even more reduced area, that of Suffolk alone.

Since the English shire equates to the continental county, the position of earl had become more akin to that of a count. Hence the female title countess, and not the more logical earl-ess. And since there are more shires than there are regions, more earls could be created as reward for exceptional loyalty. But then to curb their power, they were reduced to quasi-sheriffs and given sheriff’s administrative duties. Meanwhile, the annually appointed sheriff (shire reeve) became more akin to Chief of Police. Thus, while by 13th century the earl in status was second only to the king and his princes, he had no more power and wealth than many of his best barons.

Marquess and Marchioness

In origin, this hereditary title was applied to a noble who held the march lands, i.e. on the borders between countries. It was very much a military position, his duty to be the first line of defence. It equates with the German margrave.

The first English marquessate to be created was that of Dublin in 1385, given to Robert de Vere, 9th Earl of Oxford. He was later created Duke of Ireland by Richard II which caused a winter of discontent. The marquessates of Dorset and Somerset followed in 1397.

Duke and Duchess

A hereditary title of the highest nobility, introduced in England by Edward III for his eldest son, Edward the Black Prince, created Duke of Cornwall in 1337. The dukes of Lancaster and Clarence (from Co. Clare in Ireland) were created shortly after.

In the following century and a half the Plantagenet kings created 16 ducal titles (Cornwall, Lancaster, Clarence, Gloucester, York, Ireland, Hereford, Aumale, Exeter, Surrey, Norfolk, Bedford, Somerset, Buckingham, Warwick and Suffolk) though only four remained after the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, those of Norfolk, Suffolk, Lancaster and Cornwall. More have since been created.

The Game Board

To win the Gentry Game the Player must climb the above-defined Ladder. But in order to climb the Player must first acquire and accumulate the smallest divisions of the Game Board. We’ll call them squares although they seldom were.

But first a word about moveable wealth

While in probate terms, the deceased’s estate includes both real estate and moveable assets, in the Gentry Game the latter did not count. In fact, it was better not to have too much of the latter since to fund the never-ending wars a tax was applied upon that very same wealth. So the more one had of gold plate and fancy furs, the more tax one paid. Since one could not enjoy it to the full, one had best invest it in something more lasting. In land.

The Land and its Divisions

Celts

Long, long ago, in the days when a warrior’s sword was pulled from a stone (actually two stones, bronze being an alloy of copper and tin) the people we’d one day identify as Celts made a start on dividing the land we now know as Britain. They divided it into chiefdoms, the boundaries providing a fence over which to fight. Within the chiefdom, the farmers divided the land again – into fields and pastures, now called farms.

And so it remained for a thousand years, the fought-over borders being proclaimed in stone.

Roman

Then from the south, across the Channel, arrived the conniving forces of Rome. Conniving because they came offering friendship and equal status yet as soon as that generation was dead, they turned and bared their dominant teeth. Yet they did little to change the land divisions. They accepted the lines marked by the Celtic chieftains and marked out their estates where the Celtic farmers had marked theirs. These estates they leased to investors ‘to farm’ on behalf of the empire.

Four centuries later, exit the Romans, enter the Saxons, Jutes and Angles.

Anglo-Saxon

Finding established boundaries, the newcomers left the estates mostly as was. As with the Celts before them, the larger estates became small kingdoms, not even petty, more like chiefdoms. And as with the Celts before them, these petty kings waged war over the boundaries and in short time a handful of the more belligerent and ambitious, aided and abetted by their gods, had conquered their neighbours and gathered their lands – although they allowed the defeated former petty dynasty to remain in situ and administer what had been their land.

Thus England, once divided, was again united – at least into the seven kingdoms latterly known as the Heptarchy: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Wessex and Sussex.

Vikings

Although the Vikings subjected these kingdoms to rapine and terror, yet they were the impetus to further union. King Alfred of Wessex taking the lead, the kingdoms united in common defence. Yet they could not defeat the invaders entirely and Alfred was forced to concede East Anglia, east Mercia and Northumbria to the Danes, as the Danelaw.

Shires and Ridings, Hundreds and Wapentakes

To aid in defence against the Vikings, Alfred and his sons divided the English half of England into shires. The shires mostly followed the previous borders. Within the shires the land was further divided into hundreds. The hundreds comprised many manors, all anciently bounded. They once had been the Celtic farmer’s farm.

The Danelaw too was divided, but first into multiples of 3 known as Ridings. These remain in both Lindsey (part of Lincolnshire) and Yorkshire but in Norfolk and Suffolk, having been nominally reclaimed by Alfred’s sons soon after the Danelaw’s formation, there now is no sign of them. The ridings were further divided into wapentakes, called hundreds in Norfolk and Suffolk for the same Alfredian reason. In Norfolk, and probably repeated throughout Danelaw, the hundreds or wapentakes were further divided into leets, four per hundred (founded on personal research). This means of land division fitted neatly with Norse ideology. But while the hundreds might follow pre-existing borders, as far as is known those of the leets do not. By the time of the Domesday Survey those leets had been further divided to manors.

Note: despite we now have Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, the lands of the former Danelaw were not part of the shires and to this day Norfolk and Suffolk remain named as counties.

Because in Norfolk and Suffolk we do things differently!!!

Village, Town, Manors and Parish

Manor

At its most basic a manor is an area of land managed as a unit. It is the home of the mesne lord, i.e. Lord of the Manor. In the Domesday Book it is also called vill or township. Here township should not be confused with a town, i.e. a hub of commercial and residential activity.

Village

These come in two types: the evolved and the created.

The evolved village dates probably to early Anglo-Saxon times, being a loose cluster of houses, each house with a half-acre or so of land attached. It is a typical Germanic structure best known as a hamlet. Beyond the individually-held ‘yards’ were the communal-held fields. These were worked on a strict rotation, so as the years progressed each family worked soil both good and bad. Found in the Domesday Book populated (almost exclusively) by freemen.

The created village, however, first appeared waaaaay back, probably even before the Neolithic. (See Skara Brae). They are evidenced in Bronze Age; in Iron Age, they sit upon every low and high hill. They are a natural expression of we humans, who like and need our neighbours’ company. But a new type developed in England under Roman rule: the clustered houses of estate workers. These continued to function through the Dark Ages, into the Anglo-Saxon times and on to the Norman and Plantagenet and … on. In the Domesday Book they are populated with ‘villagers’, manorial workers.

Normans

From the day when William trounced the English, no one but the King of England was allowed to own land. (This still is the case, though few people realise it: you might own your house, but the Crown owns the land. Humph) Everyone, from duke to peasant, was a tenant.

In the aftermath of 1066, William divided England into manageable portions and awarded them to his loyal followers. This might give the impression that every acre of land changed hands. It did not. What the Church had held TRE (in the Time of King Edward), the Church held still TRW (in the Time of King William). Mostly. But now they held it off him. Personally, in return for x-number of knights when called upon to supply.

For the most part, King William took as his basic unit the manor or vill. And in the process of dividing and allotting he kept huge chunks to himself. He kept most, but not all, of the land previously in Edward Confessor’s hands. He kept most, but not all, of the land made forfeit by rebels – and the 20 years between 1066 and Domesday had witnessed more than the occasional uprising. He kept most, but not all, of the lands surrendered by English thegns when fleeing the new regime (many went East, seeking asylum in the Scandinavian, Germanic and Slavic countries). Ditto of those lands surrendered by the few French, Flemish and Breton lords who soon discovered, by holding estates in both countries they now had a conflict of interests.

Tenants-in-Chief – the Barons

William honoured his followers with grants of the newly acquired English lands. Whether Norman, French, Flemish, Breton or Spanish, whether duke, count, knight or something humbler, all were tenants-in-chief. And tenants-in-chief, as noted above, were barons.

Mesne Lords

Though the honour of most barons were restricted to manors in 3-5 shires (or counties, see note above) for a handful of men – the magnates who served as the king’s advisers; earls for the most part – held manors in every English quarter. But no man could manage such vast holdings alone. So as with the king, the magnates particularly (but lesser lords too) divided their lands and awarded them to their own loyal followers. Some – those kin to the magnates: his younger brothers, his cousins, his illegitimate sons – might be awarded such swathes of land that they too found it convenient to divide and sublet. These tenants were known as mesne lords.

The Basic Building Block of The Gentry Game

While it was the manor that provided the oomph up the Ladder, the manor was not to be used in the Game Plan. Remember, the patrimony must remain intact.

Acquired lands

Remember, too, that it was best not to hoard moveable wealth; it was best to invest it in land. But there were times when the mesne lord was in need of funds to buy a new suit of armour or to pay for his son’s education and his daughter’s wedding. Then he had no option but to sell. But never his manor. Just a few acres, a field or a meadow. Even that he’d be most loath to do since the ongoing income from leasing out fields was what kept his hands from getting muddy. But a time comes when needs must. And he’d always find an eager buyer because, as noted, no one wanted to hoard moveable wealth.

So, the mesne lord – the Player on the starting rung of the Game – would buy acres to be rid of his taxable wealth (seldom a manor at this stage of the Game) and sell them again when he had need of the funds. In such a way, if he proved a wily player, he’d begin to accumulate a number of small ‘squares’ on his Game Board. His intent was to buy these ‘squares’ within easy travel of his manor. Though once bought he’d lease them, who wants to travel across country to collect the rents.

Marriage, a sub-game

Having acquired a few acres, the Player could now move to the next stage of the Game. Marriage. Without at least one foray per generation into this ‘sub-game’ there’d no heirs to which the patrimony could pass – intact or otherwise. But in the Marriage Game lurked a couple of snakes. Dowry and Dower.

Dowry and Dower

Now a) interchangeable; b) muddled and confused

Yet in the prime days of the Gentry Game they were marked by distinct and vital differences.

Dowry

This encompassed anything brought to the marriage by the bride. It could include the silver spoons that now have become a family heirloom. It did include land – depending upon level of play, anything from a few acres to a few manors.

We of modern minds object: Has the bride no worth of her own, that her value must be bolstered by that of the land? But we miss the point. From her family’s perspective, the land portion of her dowry was to ensure her survival, no matter what a wastrel or traitor her husband turned out to be.

And for every acre brought by the bride, the husband was expected to equal it. As dower.

Dower

Dower was the land the husband’s family settled upon the bride. By law it had to be a third of the husband’s holding – at time of marriage. This too was to ensure her survival no matter what happened to the husband and his land. He might be beheaded, his lands forfeit, not a penny or a mark left for her and the children – but at least she still had her dowry and dower land.

This dower land was hers to do with as she wished. She could gift it to the Church to pay for perpetual prayers for her parents. Or she could use it as dowry for her daughters. She might grant it to her younger sons, those Gentlemen who wouldn’t inherit the main portion of land. It was hers. Of course, she could also combine it with her husband’s estate, the entirety than to be held by them both in jointure. Her choice.

Since one of the aims of the Gentry Game was to pass on the patrimony (inherited land) intact, the land acquired by tax evasion (invested wealth) was the ideal means of providing the dowry required for the daughter and the dower required for daughter-in-law.

The Heiress – the cheat

While younger sons might hope to inherit the mother’s acres, the eldest son surviving at his father’s death would inherit his father’s full landed wealth. If no sons survived, then it would be shared between his daughters. And if no daughters survived, then it would be shared between the deceased’s brothers. And if the deceased’s brothers were also dead, then it would be passed to their sons. If they had no sons, then it would go to the deceased’s sisters. &c, &c, &c down through the gene-chart, which was why genealogy was so important. It was not a curiosity of one’s forebears.

To find a bride without brothers was to be doubly blessed. She was an heiress! Which meant when her father died his entire estate would pass to her husband. The land then would be added to his own and passed to his eldest surviving son. Estate expansion achieved in one easy ‘I do’. This was a major gain in the Game.

But the heiress might bring with her yet other blessings – the family’s inheritable titles.

If her father was a baron, holding land directly off the Crown, then so too would her husband become. If her father held an inheritable title – viscount, earl, marquess – that too would be passed to him. In the Gentry Game to marry the heiress was like playing a ‘cheat’. Though it wasn’t always possible at the time of marriage to know what the bride was to become.

While generally the son & heir was married late in life – ‘Let’s hold onto that dower land as long as possible; we need the income’ – a daughter might be married obscenely young. She had no other economic value so why hold onto her – ‘Costing us money with her demands for a social whirl, fancy foods and posh frocks’. Thus, she might have five older brothers when she weds, with no hint of her ever becoming an heiress. And one does not kill one’s in-laws for the sake of a title and land. Well, not and get caught, that would be just too dishonourable, a guaranteed slide down the snake.

To Repeat…

In dodging the taxes by investing wealth thus acquiring acres, the Game Player had the wherewithal to provide dower for daughters-in-law and dowry for daughters, thus helping to provide the essential heir for the passing intact of the Player’s patrimony.

The daughters, like ludo counters, carried landed wealth from father to son-in-law.

The ultimate catch, i.e. the cheat, was the heiress. Not only did she double the family’s estate, but she also might be the bearer of the much-desired titles. But a bride only became an heiress upon the death of her brothers, and the father might remarry late…

An example of this was when Sir Walter Jernegan married Isabella, daughter of Sir Peter Fitz-Osbert of Somerley Town, Suffolk (Somerleyton). He hadn’t a notion of what a catch he had found. Indeed, the full import was not to be realised for another two generations.

I trust you found this little venture into Medieval History, useful and enlightening 🙂

Quite informative…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you 🙂

LikeLike

Pleasure

LikeLiked by 1 person

Goodness me it’s all very complicated – I’ve heard most of the words and titles of course without any real sense of what they all meant 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s this idea that the past was much like it is today, but with less technology. It was not. And to understand the motives of people then living, we need to understand the social milieu.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well that’s as clear as mud then, like the board game analogy though, will re-read when the fog clears, I.e. after gin o’clock

LikeLiked by 1 person

And people believe the Middle Ages were just like now, with more basic technology. And today we Brits are still class conscious… but, like, working class, middle class and upper class. Greatly simplified, and even this amount of stratification we try to deny 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well that’s as clear as mud then, like the board game analogy, will have to re-read when the fog clears, i.e. after gin o’clock

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmm, a double comment. Strange. Cn we blame it on the gin?

LikeLike

Probably due to my iPad not informing me when a comment has been posted leaving me in a state of uncertainty, although I should be used to that after years of experience

LikeLiked by 1 person

No probs. I don’t mind receiving it twice 🙂

LikeLike

A good overview of medieval England’s hierarchies. I have thought about writing some articles on some interesting points in the history of medieval Europe, but I’m not sure if they would be read, and I tend to mostly use my blog for fiction and poetry now. But I certainly enjoyed reading this one. Well done 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Joanne. As I noted in the preface, this was originally written for a dedicated history site. Everything I posted on that site and referenced, with online links were possible. It had no great following, and you it did have ample views.

But I closed to down to contrate on fiction.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well put together! I can never keep all those titles straight, and this reminds me why, at least in part: because they differ across countries and keep changing over time. I’m sure, though, that I never realized that “march lands” were the source of the marchioness title: so interesting!

You say a few times that the gentry didn’t want to amass too much moveable wealth because they were taxed on it, and that it made more sense to invest that wealth into land. I’m assuming that they’d keep at least some of that fancy stuff as high status markers, and I know that one way of transferring expensive goods was in gift exchanges. But I’m curious: if everyone was more interested in land than moveable wealth, who could the gentry convince to give up their land for gold and jewels and such stuff? I feel like I’m missing a part of the game, here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Several of the kind pre-Tudor, were rather keen on invading France on the grounds they had a legitimate claim to the French throne. But invadion costs money, These kings imposes=d taxes, as I say. Also there was King Richard the Lionheart who only stepped on English soil twice, the second time was to raise taxes to pay for his ransom. Since these taxes were on moveable wealth, nobody wanted to accumulate. But what happened when the son went to university, or went to war, or a daughter was married, and money was needed? Then sold off their least attractive parcels of land. The outlying fields. The least productive. Plus at all times there were families were struggling, eager to off-load land. Especially after the BlackDeath allowed the farmlabourers to demand a working wage. So… there’s your answer. They climbed the ladders, and slithered down the snakes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do enjoy the analogy of snakes and ladders… So thank you, I’m getting a better sense of the full picture now. Am I understanding you correctly,that by moveable wealth you don’t mean gold (or not only gold?) but goods like jewels, furniture, expensive decorations, etc.? I’m assuming the university and most others would want you to pay in gold. So there must have been merchants willing to pay gold for goods, right? Presumably only if they could sell it to someone else for even more gold. I guess selling such things up the ladder? What an interesting and complicated economy that must be, in such high-end goods that only a few households in the country might afford them.

LikeLike

Actually, England had had a coin economy since before it was England. The mark was the measure, if you like to call it that, worth (if I remember ) 6s 8d… 3 to the £. But the legal tender was the peny. You can imagine how heavy the coffers could be with 80 pennies to the mark! But yes, gold was also used. And many of the lords, including the kings, would make gifts of gold plate to their more treasured and valued household members… who usually were family or in-laws.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Took me three sessions and two days to read this but read it I did. Fascinating. You definitely make history fun, Crispina!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is rather long, isn’t it. That’s why it was confined to my history site, where only the keen history readers would find it. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey. We have the choice to read it, right?

It was too interesting to put aside!

LikeLiked by 1 person

And I notice you’ve tweeted it too. It’ll be interesting to see what response that gets. I didn’t tweet it: I have several medieval historians follow me

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I did. My posts automatically get tweeted and honestly, I have no idea if any result in someone reading them (and don’t care about my stats which would tell me… and now I’m curious so I have to go see! – ad neglible… one per post, maybe)

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very detailed and full of cool info! Any American should read a cheat-sheet like this before diving into a lot of English works. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just wish I could have made it shorter. But to abbreviate would be to confuse. Glad you found it informative! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person